In late 2009 I acquired a small amount of funding to develop ‘Queer Noise’ – an online exhibition for Manchester District Music Archive that aimed to lift the lid on LGBT music-making and club life in Greater Manchester from the sixties to the present day. The exhibition would harness and contextualise scanned ephemera, such as posters, flyers, photos and press articles uploaded to MDMArchive by members of public all over the world, in addition to my own collection of artefacts, which I had been digitising for a number of years.

Launched in 2010, ‘Queer Noise’ now contains over two hundred chronologically ordered images and written recollections, and continues to grow as more and more people share their memories. A selection of these artefacts will form the basis of my short presentation to the LGBT History Festival in February.

In my talk for I will be examining three key points in the city’s LGBT music history: the birth of punk in 1976; the house music explosion of the early 90s: and the alt-gay scene which developed a decade later as a response to the homogeneity of the music on offer on Canal Street (Manchester’s gay village).

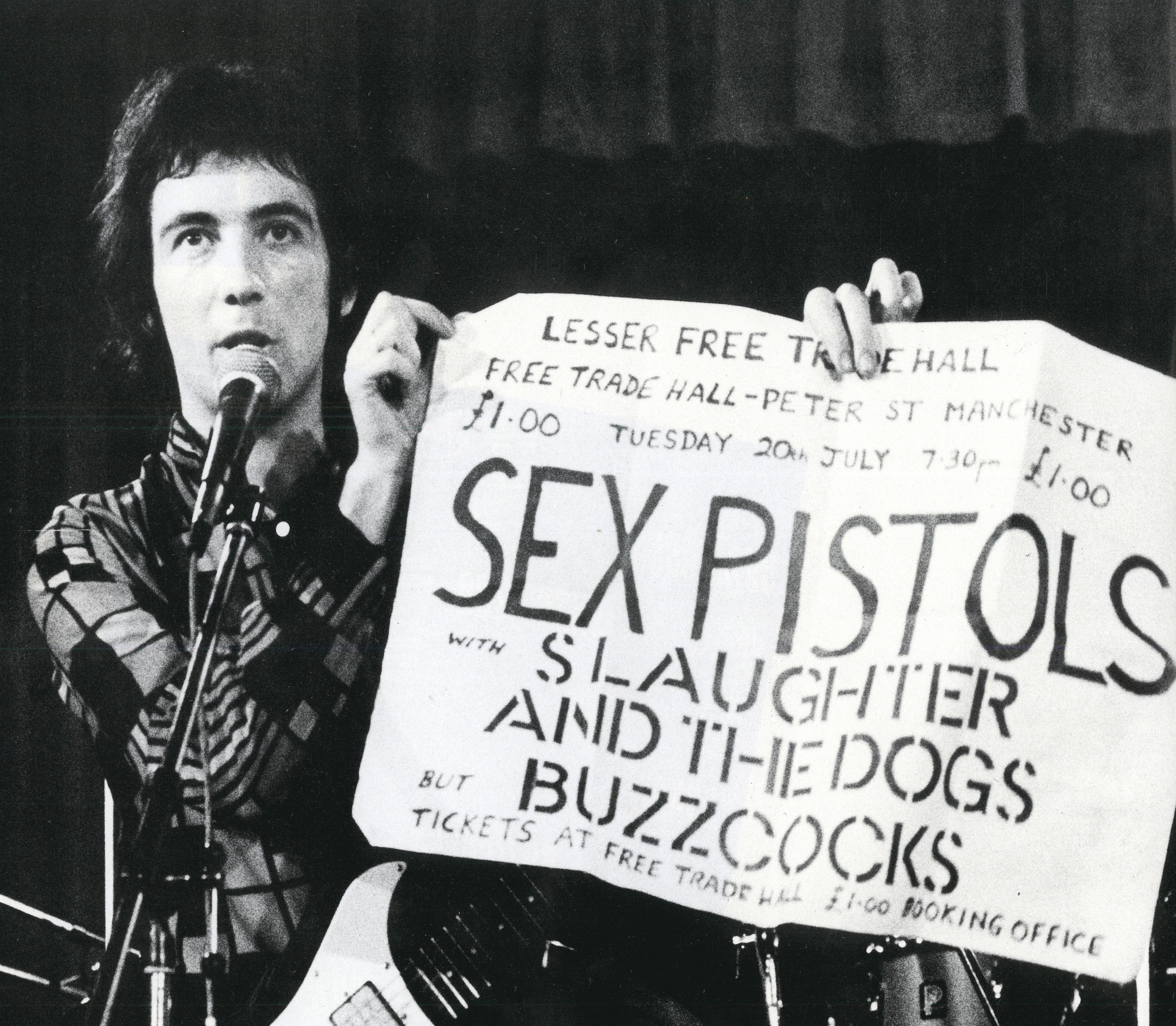

In the summer of 1976, punk hit Manchester following the Sex Pistols’ pivotal brace of gigs at the Lesser Free Trade Hall. Misunderstood by many as an aggressive, negative force, the early punk scene in Manchester celebrated difference; fostered a DIY approach to creativity and self-expression; and created a tightly knit music community, which (for the most part) welcomed LGBT young people. Pete Shelley of Buzzcocks, who co-promoted the Pistols’ second gig, was openly bisexual and sang about romantic experiences with both men and women in a very straightforward way. But ‘76 was also the year in which James Anderton began his tenure as Chief Constable, marking the beginning of a sustained period of harassment of Manchester’s LGBT community by police. Punk historian Jon Savage said of this time, ‘Manchester felt under lock-down then: if you were out late at night, you’d get stopped at least twice a week. It wasn’t just gay people, it was anyone who looked and acted different.’

Fast forward to 1990 and we see the launch of Manto on Canal Street – a sophisticated European-style bar that deliberately flouted the prevailing ‘behind closed doors’ culture of gay venues by installing full height plate glass windows. Thanks to DJ Tim Lennox, house music took hold at Central Street’s gay-friendly Number 1 Club, which in turn led to the birth of Flesh at the Haçienda – a wildly successfully Ecstasy-fuelled house and garage night flagrantly billed as ‘Serious Pleasure for Dykes and Queers’. It was during this time that the city was dubbed ‘Gaychester’, the first Mardi Gras happened, Canal Street boomed and Manchester City Council truly cottoned on to the potential of the pink pound.

Flesh lasted until 1996, spawning many copycat club nights and, along with the Number 1 Club and Paradise Factory, was responsible for the making house music the dominant sound of ‘Gaychester’. But by 1998, some of the same DJs, promoters and club goers that had inspired the house boom were growing tired of the commercialisation of both the scene and the music. At this point, LGBT club nights boasting a more eclectic soundtrack spanning funk, soul, disco, hip hop and indie began to emerge. Club Brenda and Homo Electric were at the forefront of this movement. Like the punk scene that had come before, these clubs celebrated difference, with flyers boasting slogans such as ‘Music is life, gym is the coffin, be ugly‘.

As well as flyers, posters, gig tickets and photos, my presentation will include some unseen footage of Manchester’s gay clubs, plus excerpts of oral histories captured exclusively for the festival.

If you would like to add any artefacts or recollections to the Queer Noise online exhibition, please register to become a member of Manchester District Music Archive here and start sharing your history. Alternatively, you can email: info@mdmarchive.co.uk.

Comments by Abigail Ward