01. Europa Cinemas Trailer

02. George Martin – And I Love her

03. Hi-Voltage Orchestra – Midnight Blue

04. Dave Grusin – Three Days of the Condor

05. The Jackson 5 – Can I See You In The Morning?

06. Brian Bennett – Solstice

07. Charles Earland – I Will Never Tell

08. Mo Foster – Stateside II

09. Bob James – Nightcrawler

10. Fat Gaines Band present Zorina – For Your Love (Diablo Edit)

11. Lonnie Liston Smith – A Chance For Peace

12. Leo’s Sunship – Back For More

13. Lambchop – Give Me Your Love

14. Pete Dunaway – Supermarket

15. Soul Sensation Orchestra – Faded Lady (Instrumental)

16. Robert Upchurch – The Devil Made Me Do it

17. Bob Welch – Don’t Let Me Fall

18. Marvin Gaye – I Want You (Vocal & Rhythm Version)

19. Freddie Hubbard feat Jeanie Tracy – You’re Gonna Lose Me

20. Johnnie Taylor – What About My Love?

21. Barry White – Sheet Music (US Promo Instrumental)

I never really wanted to be a DJ. I have always collected records and owned a turntable, but for much of my younger life I focused on writing my own songs rather than playing other people’s. That changed in 2007 when my friend Kate – then bar manager at Cornerhouse – asked me to do a mix of rare film scores for her to play at work. A short time later, she invited me to DJ on a Friday night, and so began a six-year tenure as a handmaiden of the decks.

On my first night, trembling with anxiety, I pitted my wits against a crackly Numark mixer and Cornerhouse’s famously sensitive limiter, a device that would cut the sound dead throughout the whole venue if it didn’t care for your tunes. I triggered it three times. Kate explained I had to balance on a stool and bash it with a tray to achieve a reset.

I called my night Big Strings Attached and indulged my love of all things stringed, from symphonic soul to cinematic pop, and of course, plenty of soundtracks.

Initially I played at the top of the stairs in the café bar. I would lose myself watching the weather out of the window while first dates and last orders rippled pleasantly around me. I stood up to DJ behind a makeshift wooden booth on wheels. It would be rolled in through double doors at the start of the night, reminding me for some reason of a coffin sliding into the furnace.

When the managers eventually agreed to replace the £50 Numark with a Pioneer DJM 750 mixer, the decks would no longer fit in the coffin, so I ended up sitting at an ordinary table. Pros: I could take the weight of my feet, always sore from a full Friday working the counter at Piccadilly Records. Cons: I became too accessible to punters who needed to chat.

From that point on, people were able to draw up a chair and talk to me. And of course, there was no escape. Many sordid sob stories and unsolicited confessions were shared, leading inevitably to dead air and flunked mixes on my part.

There was Elsie, still angular of cheekbone at 80, whose bright eyes would fill with tears when recounting her days treading the boards at the Royal Exchange; there was Terry, who claimed I was the only person he could talk to about his desire to have gender reassignment surgery; there was Dr Octopus, a GP with broken facial capillaries, whose tentacles, come 10pm, would brush across the buttocks of his always much younger female companions. There was Robin, who sometimes noticed blood in his stools.*

I hate talking to people when I am playing records. It’s a social no man’s land. You can’t get meaningfully involved in either the conversation or the music. Even when close friends came in to help me through a shift, I found it awkward. My heart would sink a little.

I tried for a time simply to exist within my headphones, strings blaring. But people would still come and talk to me. It was more disturbing to confront their wordless gaping mouths than to listen to their problems.

A sweet looking boy called John was a regular feature for a while. He would slope in early doors, always nicely turned out. He’d been an obsessive clubber and house music collector in his teens. Intermittently he would talk in fully formed sentences about college or music, but much of the time he spoke in fragments, little blurted scraps. He wasn’t drunk. I never saw him with a drink. Someone hinted that he’d been flung through the doors of perception so forcefully whilst on acid or ket that he’d never quite made it back. Sometimes he did the crossword next to me, shouting out random words. One night I picked up the newspaper after he left and discovered he’d filled in each blank word with my name.

Very occasionally, perhaps once a year, someone would want to talk about the music I was playing. This was a genuine delight. I have no issue with people who want to talk about music. Provided their taste is immaculate, like mine.

In later years I was moved downstairs to play in the window by the door. The ground floor had a different atmosphere, a transient crowd, no food. I campaigned weekly to get candles on the tables and lights dimmed.

By now I’d toughened up a bit. I had strategies to deal with ‘sitters’. Downstairs, it was less heartbreak, more hassle. I still have nightmares about one night when the Rocky Horror Show was on at the Palace. The bar was heaving with stroppy hets in fishnets thrusting their pansticked faces into mine because I wouldn’t play ‘The Timewarp’.

Another time, over Christmas, a paralytic Santa on Oxford Road pressed his bare arse up to the window millimeters away from my face. I can still see his sad sack dangling.

Setting up the decks was less convenient. I had to carry my Technics, mixer, CDJ, and monitor down several flights of stone stairs that ran from the top to the bottom of the building. This area of Cornerhouse had a very particular smell: bleach, hops, sweat and something all of its own. All buildings have their smells, like people.

During the final year, appalled to discover that Cornerhouse was soon to be demolished, I began to experience an odd feeling on those stairs, almost as if I were being watched fondly by a future version of myself as I hoofed gear, outstretched foot holding open the fire door, cables spilling out of pockets. A spasm of intense nostalgia for the building not yet lost.

The bar staff at Cornerhouse were, almost without exception, kind, creative, funny. Working the pumps were writers, music producers, filmmakers, trainee psychologists, ceramicists, cartoonists, fashion designers. They were never stingy with the anaesthetic and if I was a good girl I could pick a leftover brownie at the end of the night. I did, for a short period suffer a rather painful crush on one particular bartender, who basked in my discomfort like a tabby on a windowsill.

Rory – a security guard, became one of my main allies. He would help me with my gear when my back was fucked. He had a sixth sense for when I was being mithered and would hover around diplomatically. He pulled me out of myself when I was red wine-glum (often), and nearly always had a Blue Riband going spare for a counter jockey who’d skipped tea. Rory’s most requested tune was Shirley Bassey’s version of ‘The Hungry Years’, which was absolutely fine by me.

There were celebrity sightings, both real and imagined: Eric Cantona, Damon Albarn and Willem Dafoe all came in during Manchester International Festival. One of these luminaries was, according to staff, foul tempered and condescending. Can you guess which one?

Sometimes, on the lonelier nights, my grip on reality dangerously loosened by Malbec, I would imagine being visited by the stars whose records I was spinning. Donald Fagen popped in regularly to ‘work a little skirt’. Nina Simone stopped by, fuming, because front of house had asked me to turn down ‘Baltimore’. The young Michael Jackson would crawl under my table, eyes brimming, during ‘Who’s Loving You?’.

In 2013 my time at Cornerhouse ended in the style of a long term lesbian love affair. Both parties claimed in public it was a mutual decision. And we’re still friends.

People who are concerned about the fate of the Cornerhouse building and ‘Little Ireland’ may be interested in attending the first Manchester Shield meeting at 6.30pm on Thursday 14th April at the Friend’s Meeting House.

*The names have been changed to protect the guilty.

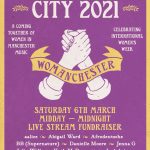

Comments by Abigail Ward